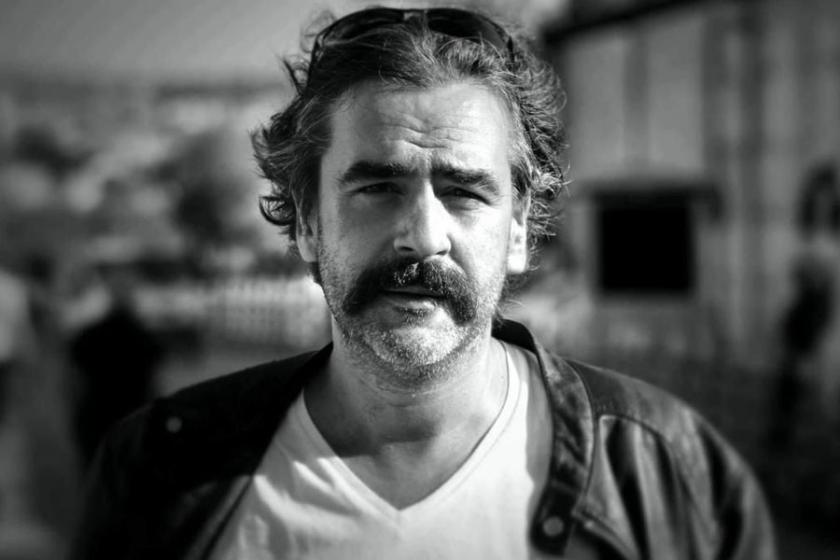

Imprisoned Journalist Deniz Yücel: Why should I regret doing my job well?

Fatih Polat speaks to fellow journalist Deniz Yücel, who has been imprisoned for 11 months without any formal criminal charges brought against him.

18 January 2018 09:34

Fatih Polat speaks to fellow journalist Deniz Yücel, who has been imprisoned for 11 months without any formal criminal charges brought against him.

Fatih POLAT

Since he was detained he has been targeted by senior state figures who have made serious accusations against him and kept him imprisoned at Silivri Prison without even an indictment. So what kind of journalist is the Die Welt Turkey Journalist Deniz Yücel? And what is he like as a person?

Deniz Yücel has previously come to the attention of the newspapers about his imprisonment. We asked him about his imprisonment and more. Here are his responses.

You have been deprived of your liberty for the past 11 months and the indictment still has not been prepared. What do you have to say about this situation?

They might have forgotten. Or the instruction they are waiting for has not been sent. There is no need to labour this point with Evrensel readers. In any case, I will give you an example of a new story I wrote in Turkey. One and half years ago I spent some time on the IlhanComak case. I visited his family who lives in Izmir. I spoke with his lawyers and told his story at the Die Welt newspaper at which I was working. At the time Ilhan had been in prison based on ridiculous allegations and without any criminal findings against him for 22 years. Later he received a life sentence. He recently published a new book of poems. Both the history and the present day reality of this country is full of stories similar to this. I cannot minimise the injustice done to me. Every day that is stolen from my life, which I could have spent with my partner Dilek, is valuable. However, I don’t want to claim that I am the worst victim of this political establishment.

It looks like, the Turkish government is trying to repair its relationships with Western Europe. How do you evaluate these efforts?

The government may have realised that it does not have the luxury of fighting with everybody. However, I don’t think these efforts will bear any fruit. Because the current government is against the West in two ways. Firstly, this government blames the West for all domestic problems as a way of crisis management. Secondly, this government ignores so-called ‘western values’ which are in fact universal values.

In any case, do you think this improvement in relations will impact your situation?

My French colleague, Loup Bureau was imprisoned for two months in Turkey. In September after he was released a story was printed in the French press saying that “the two governments have negotiated and that in exchange for the journalist Bureau’s release, France had agreed to approve an arms contract for air defence to Turkey”. From my monitoring of the situation, this allegation was not denied. And during Erdogan’s recent visit to France, an arms deal of this type was signed. Additionally, whilst Macron was, on the one hand, shutting down conversations about Turkey’s possible membership of the EU, he has also been simultaneously using the opportunity to sell whatever he can to Turkey, ranging from meat to planes. I don’t know, maybe this is just the way things work. But I don’t want my freedom to be tainted by German tanks and arms. Neither do I want my freedom to be tainted by the return of those who have previously been co-conspirators with the government (and should be tried) but are currently seeking refuge in Germany. I will not be a part of any dirty deal.

You said that you rejected the uniform whilst in prison.

Yes, I said ‘never’. There is nothing more to say.

So of all the work you have done until now, which have you liked the most?

Let me tell you the most interesting in terms of Turkey. It was the Gezi demonstrations. Whilst I had been doing intermittent bits on Turkey before this, I had been slightly distanced from events in Turkey. And then Gezi broke out and I tried to monitor developments simultaneously on social media. And then it was the last few days of June when I told my chief editor that I was going to Turkey whether or not he would send me, whether or not he pays for the expenses. At the time taz had a Turkey reporter. I had noticed that something beyond the usual events was taking place. But this wasn’t enough. Anyway, I came and from the first day I took over all the news from inside the park. I was supposed to stay 4 days, but I stayed 6 weeks. During this time I went to Ankara and Kayseri, sorted out some business organising work on a book in Germany, and then returned to Turkey. The book is called “Everywhere is Taksim” and can be summarised as being “a portrait of the other 50%”. It was translated into Italian but unfortunately, it is not available in Turkish. Anyway, strangely a significant number of the journalists reporting on the Gezi demonstrations were in a similar position. Basically, those journalists working in the German media who were not reporters on Turkey but who because of interest, emotional attachment or the love of their country returned. This situation could have been a new story in itself for the Turkish media: ‘German journalists return to eat tear gas because of their love for their country”

In your opinion what are the most important professional traits journalists should have?

Let me restrict this to two or three things. Firstly, they should be just. So, they should not ignore those things that contradict their own views or stories. Secondly, they should observe events as closely as possible but when analysing distance themselves as much as possible. And one more thing: they should not be content with simply “he says she says” and should go beyond this to research who is right and wrong. Regardless of the subject or who I am talking to I have always tried to apply these principles; whether it be the refugees about to board boats in the Mediterranean; speaking to armed militants behind barricades and handmade explosives in Sur and Cizre; those who lost loved ones in the Ankara station massacre, where I was too embarrassed to ask questions of those waiting outside the hospital; listening to the stories of families whose children were captured by ISIS; or watching whilst people gathered outside Ataturk Airport to listen to the president speak. Of course, the verdict belongs to the reader.

Let’s flip this on its head. What shouldn’t a journalist do in the course their profession?

You cannot be a journalist if you worry that about things such as “if I run the particular story, or if we highlight that story the boss’ relationship with the government will be negatively impacted”. You also should not say “but our readers would not approve”. Every journalist, like every individual, has a worldview. And so they should. Because part of the journalists’ role is to analyse what has happened and provide commentary. Journalists should have values that they defend. But they should not behave like foot soldier for a particular case.

Do you follow the news from prison? Do you hear the sounds of solidarity?

Nowadays I receive one newspaper a day. Thanks to friends in Germany who send a newspaper daily, which I receive even if it is a few days late. Over time I have got a television. My dear lawyers also keep me update on some of the developments. In that respect, I am not completely disconnected from the world. Although I do not hear about all the expressions of solidarity, I do hear about most of them. I am eternally grateful to colleagues and friends in Turkey and around the world, and those who have written to me for not forgetting about me and my imprisoned friends.

A short time ago isolation was ceased. How has this impacted your life in prison?

Actually, isolation has not ended completely, it is simply less harsh. Before the state of emergency, there was the right to chat with people, exercise with others, courses etc. All these have been suspended since the emergency state. But of course, having spent the past 10 years alone it is really nice to be able to talk to someone. Most recently I am staying with journalist Oğuz Usluer who used to work at HaberTurk. Our cells are separate but we can have breakfast together and during the day we pace up and down the yard surrounded by layers of barbed wire. But in the widest sense of the term, from the Left opposition prisoners, the person who has both been in isolation for months and has only been able to see his lawyers for one hour a week has been Osman Kavala. Even though I only ever met him once, I would like to send him my greetings.